Public Debt’s Balancing Act: r vs. g

Why This Classic Economic Rivalry Shapes Our Debt Future

The US faces a heated debate over fiscal stability because of soaring debt, rising interest costs, and political gridlock blocking solutions. With key tax cuts set to expire and the debt ceiling looming, the pressure is mounting to find a sustainable path before the budget crisis deepens.

Few numbers spark as much debate in public finance circles as the delicate dance between r (the real interest rate) and g (the economic growth rate)—a relationship that sits at the very heart of every conversation about government debt sustainability, captivating policymakers and economists alike as they gauge the future of fiscal stability.

The relationship between g and r is central to understanding public debt dynamics and economic policy.

The real public debt problem is less about the sheer size of the debt and more about whether the economy can sustainably manage it—which depends heavily on the relationship between r and g.

r represents the inflation-adjusted cost of borrowing or the inflation-adjusted return on investments. It tells us how much lenders actually earn, or borrowers actually pay, once the impact of inflation is removed. For government debt, r is the rate the government pays to service its debt, after accounting for inflation.

g measures how quickly the overall economy (usually GDP) is expanding, again after removing the effects of inflation. It reflects the increase in the nation’s productive capacity and the value of goods and services produced.

When r>g: The cost of servicing debt grows faster than the economy, making it harder for governments to manage or reduce their debt burden over time. This often requires running budget surpluses or cutting spending to keep debt sustainable.

When r<g: The economy is expanding faster than the interest owed on debt, making it easier to stabilize or even reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, even with some deficits.

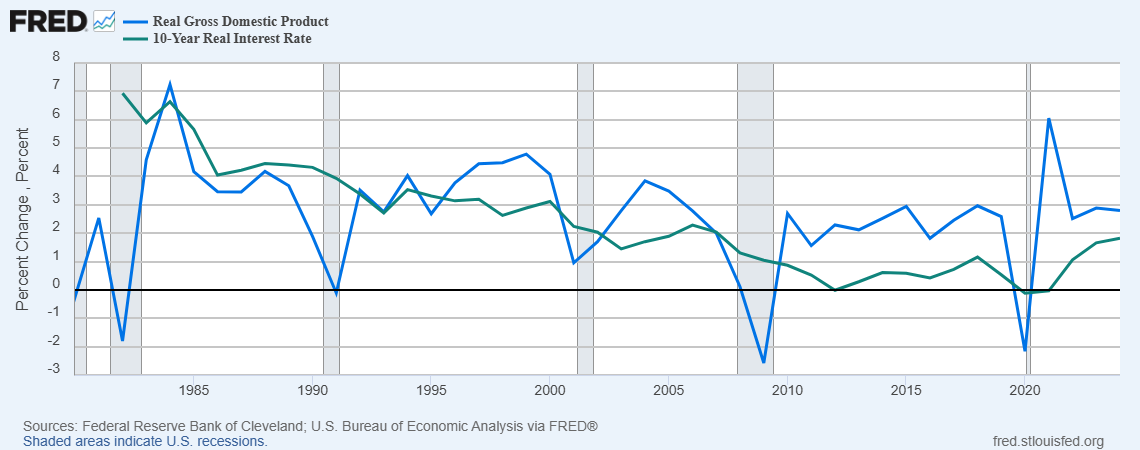

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the relationship between the U.S. real economic growth rate (g) and the real interest rate (r) has shifted through several distinct phases:

2009–2019 (Post-crisis recovery):

Real interest rates (r) were exceptionally low—often near zero or even negative—due to aggressive Federal Reserve policy and subdued inflation. Meanwhile, real g averaged around 2% per year, with some fluctuations. For most of this period, g was higher than r, making it easier for the government to manage and service its debt.2020 (Pandemic shock):

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a sharp contraction in GDP, with g turning strongly negative (about -3.5%). At the same time, real interest rates remained at historic lows, but the collapse in growth meant g was much lower than r for that year.2021–2022 (Rebound and inflation surge):

The economy rebounded strongly, with g rising above 5% in 2021 before moderating in 2022. Real rates remained low or negative, so g was again well above r during this period.2023–2025 (Normalization and tightening):

Growth has slowed to around 2% per year, while real interest rates have risen as the Fed raised nominal rates to combat persistent inflation. By 2024–2025, g and r are much closer, with some projections showing r slightly above or roughly equal to g. This marks a shift from the previous decade, where gg consistently exceeded r.

The real risk of a fiscal crisis isn’t just about how big the U.S. public debt is—it’s about the crucial relationship between economic growth (gg) and interest rates (rr). When the economy grows faster than the government’s borrowing costs, the chances of a sudden fiscal meltdown are slim. But if growth slows or a recession hits, that balance can quickly shift, making the situation much more precarious.

Don’t get the wrong idea, though: public debt absolutely matters. As debt grows, so do the government’s interest payments—which have already soared to an eye-popping $880 billion a year. The g and r dynamic may keep things stable for now, but it doesn’t erase the mounting burden of ever-increasing debt.

We're unlocking this article for everyone—dive in and explore our full range of sources and insights, absolutely free!

Our platform goes beyond headlines, offering deep macro and financial analysis plus hands-on educational resources to help you master the markets and economy.

If you found this read valuable, why not take the next step? Paid subscribers get exclusive access to tactical trade ideas, real-time portfolio updates, and actionable strategies—giving you the tools to invest with confidence and stay ahead of the curve! Join our community and elevate your market game!